"The Good, The Bad & The Ugly": The Truth About Dog Parks

I like to consider myself a bit of a movie buff. In fact, there was a time in my life when writing and directing movies was my biggest passion outside of dogs. Maybe in some way I was going to be like the next “do-it-all” Clint Eastwood. Now I write articles about dogs and take videos whenever I can – the closest I’ll ever get.

One of the most controversial topics out there is that of dog parks. I myself have admitted to many clients that I’m not generally a big fan of dog parks for most dogs. That’s really only because there are so many ways that an outing at a dog park can go wrong if a dog’s owner isn’t properly educated about the good, the bad, and the ugly sides of these encounters. We all want to find the gold - the dual opportunity for our dogs to get out some of their pent-up energy and socialize with other dogs at the same time. The truth is, dog parks CAN provide great experiences for SOME dogs; but on the flip side, dog parks can also provide highly traumatic experiences for others (like dogs that are insecure, overly dominant, or haven't previously been socialized well with other dogs before their trip to the dog park). So how do you know whether going to a dog park is right for you and YOUR dog? Let me share with you…

One of the most controversial topics out there is that of dog parks. I myself have admitted to many clients that I’m not generally a big fan of dog parks for most dogs. That’s really only because there are so many ways that an outing at a dog park can go wrong if a dog’s owner isn’t properly educated about the good, the bad, and the ugly sides of these encounters. We all want to find the gold - the dual opportunity for our dogs to get out some of their pent-up energy and socialize with other dogs at the same time. The truth is, dog parks CAN provide great experiences for SOME dogs; but on the flip side, dog parks can also provide highly traumatic experiences for others (like dogs that are insecure, overly dominant, or haven't previously been socialized well with other dogs before their trip to the dog park). So how do you know whether going to a dog park is right for you and YOUR dog? Let me share with you…

First, regardless of your dog’s individual temperament and preferences (which we will get into later), there are some things to consider when choosing a dog park. Some parks are more carefully maintained and have more regulations for safety than others. These are the kinds of dog parks you want to look for, since they are generally set up in a better way to be the most positive experience for all dogs involved. Now that's not to say that all users of the dog park will respect these regulations, but the hope is higher than what you might find in a less maintained or regulated arena.

|

|

First, it is best if the dog park enclosure itself is very large, possibly an acre or two. Having plenty of space to roam means that dogs are less likely to feel pressured by being in the same space with other dogs they may not know. In a large space, if a dog wants to be in the center of all the action he can be, but he doesn’t have to be. If a dog chooses to wander the outskirts, just sniffing and doing his own thing, he has the space to do that as well. For those dogs that may do better with dogs closer to their own size, it's even more helpful if there is a separate “small dog area” for those Yorkies that don’t want to interact with the Shepherds. To the left is a brief video and photo of a dog park on Skidaway Island that I feel has a very good setup for space.

If a dog is choosing to spend his time at the dog park sniffing and doing his own thing rather than really getting involved with the other dogs, these dogs are, to use easy terms that relate to human behavior, the more “introverted” dogs, if you will. These dogs are either not super confident around other dogs, haven't had a chance to build their dog skills yet so could be easily overwhelmed, or are just not overly social with other dogs so they prefer to keep to themselves at the perimeter for their entertainment, or closer to their humans for more support. Then you have the dogs that are “extroverts” – the ones that are running around in the center of the space with a bunch of other dogs. Maybe they are chasing toys that are being thrown for them by their owners, or maybe they are playing their version of “catch me if you can” with the other pups. Whether your dog is an “introvert” or an “extrovert” personality, being in a dog park that offers a lot of space can take off some of the pressure and make it easier for a dog to have a more positive experience. |

|

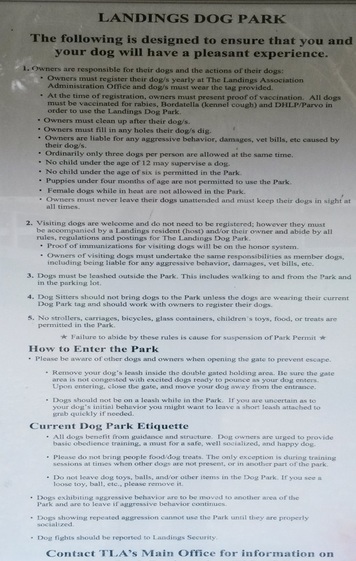

The next thing that I feel should be considered is having a careful set of regulations that users are required to follow in order to use the park. Not anything outlandish, like needing to install a GPS tracking device on your dog with all of your financial information, but simply requiring that each dog is registered to use the dog park annually, that the dog wears its yearly tag on its collar to be visible to other park users, that owners submit annual vaccine records, and that users follow dog park etiquette rules (to clean up after their dog, for owners to have sight of their dog at all times within the park, to leave the park if their dog is exhibiting any aggressive behavior, etc). There should also be a way to report any user who does not follow these guidelines, with the goal that those attending are taking accountability for their own actions and those of their dog. |

Now that we’ve covered what to look for in selecting an appropriate dog park to attend, let’s talk about what can make a dog park experience good, bad, or downright ugly…

|

THE GOOD:

When handled appropriately by the owner, visiting a dog park can be a positive and fun experience for social, confident dogs that are well-socialized to other dogs. Perhaps these dogs have been raised with other dogs in the household and had the opportunity to learn what appropriate dog play looks like. Or the owners have a lot of family and friends that have other dogs, so their dogs have had the opportunity to go for walks with or visit other dogs to learn how to read other dogs’ body language. For these dogs, going into a dog park may be likened to someone in public relations going to a mixer – a chance to happily mingle with like-minded individuals, exchange some information, and then go on their merry way (maybe having created some networking opportunities at the same time). Usually these dogs will find other dogs with similar play styles, figure out pretty quickly what boundaries those other dogs have (i.e. they don’t want to be mounted or have their heels nipped at, etc.), and be able to adapt quickly to make the interaction fun for everyone. These are the dogs that love dog parks! |

If you’re not sure how your dog may react to the other dogs in the dog park, I recommend staying outside the fence and letting your dog observe the other dogs at a safe distance. Pay attention to your dog’s body language… Is he calm, timid, or barking and lunging? Do his movements stay neutral and fluid, slow down or speed up? What is his breathing like? What is his ear-set, tail-set, and the overall shape of his body telling you? A dog that has an owner who will listen to what he is trying to say will have a better experience than a dog whose owner has her own agenda at the dog park.

Most dog parks tend to have some regular “yappy hours” – times of the day when they see more traffic and have a greater number of dogs and their owners going in and out - and there are times where there’s more of a lull – when you and your dog may be one of the only couples there. If your dog isn’t used to interacting with many different dogs of various shapes and sizes at once, planning to attend the dog park during one of the “lull” times is going to be best. Doing this allows your dog to acclimate to perhaps only one or two other dogs at a time rather than a whole crowd, and will usually result in a more positive experience.

Most dog parks tend to have some regular “yappy hours” – times of the day when they see more traffic and have a greater number of dogs and their owners going in and out - and there are times where there’s more of a lull – when you and your dog may be one of the only couples there. If your dog isn’t used to interacting with many different dogs of various shapes and sizes at once, planning to attend the dog park during one of the “lull” times is going to be best. Doing this allows your dog to acclimate to perhaps only one or two other dogs at a time rather than a whole crowd, and will usually result in a more positive experience.

|

THE BAD:

For dogs that aren’t used to interacting with many other dogs, or for dogs that enjoy their personal space, attending a dog park can be an overwhelming experience (it may start out that way, or it may keep building and building until it’s finally too much to handle). Let me tell you a story… |

When my Corgi, Scout, was a puppy, I took him to work with me at Guiding Eyes for the Blind on a daily basis. During our lunch breaks, many of the staff members took their dogs up to a two-acre fenced-in area in the woods called the “BDA” (for “Big Dog Area”) to get some energy out and to socialize. For all intents and purposes, it was a dog park where all the people attending were well-versed in canine behavior. I enjoyed being able to take Scout up there as a pup so he could socialize with other dogs (since he was my only dog in the household). Scout was the only Corgi in a group of dogs that usually included several Labradors, a German Shepherd or two, and an occasional Jack Russell. You’d think that since Scout and the Jack were about the same size that they would have become fast friends, but this was not the case. More often than not, Scout found himself the attention of the Labradors and Shepherds who wanted to play with the “big-spirited guy in a little guy’s body”. This started out all good and fine, all were happy. Scout and the other dogs would go through periods of running, then tumbling about (which I affectionately referred to as the “Corgi drop and roll”), and then taking off again. But after a while, I began to notice a change in Scout’s behavior.

Where Scout once appeared fond of this type of play, he started to become more assertive and vocal with the bigger dogs when they would cause him to tumble. It appeared he no longer enjoyed being the object of the bigger dogs’ attention. He started standing up for himself more, which is natural to a certain degree, but there were times when I felt his strong reactions were unwarranted. I realized that having this kind of experience with the other dogs was no longer helping Scout to become comfortable with other breeds; instead, it was causing him to feel like he had to become defensive all the time so the bigger dogs wouldn’t pick on the little guy. As soon as I made this realization that being in the BDA at lunchtime was beginning to have a negative effect on my dog, I decided we would no longer take part in this ritual.

Now that’s not to say that Scout doesn’t enjoy running free with other dogs anymore. As a dog owner, I just take my responsibility seriously to ensure that I don’t put my dog in any situations that are too much for him. This means that instead of running amok in a dog park with many unknown dogs, Scout spends his outdoor time with his canine friends by going on walks or hiking together, usually only a few other dogs at a time – which is what he loves and can handle. This is just who he is. He enjoys when I use him to help clients and their dogs have positive dog exposure sessions – he takes his job as cohort very seriously! Plus, when hiking or walking the dogs have something else to focus on other than one another – they wander and sniff and do other natural dog things, taking the pressure off of the dog-to-dog interaction. Scout has had a 100% success rate getting along with other dogs when using this method, and he actually looks forward to doing this with some of his best buds! For more info on how to make this work for your dog, contact me or see my article Introducing Fido to Rufus: Dog Greetings, Pressure Free!

Something else you might witness at dog parks: different breeds having different play styles. For example, we used to joke at Guiding Eyes that a Lab’s version of play is “let’s mesh spleens!” since they often can be found enthusiastically body-slamming one another; while a Shepherd tends to play herding games by nipping at heels or hocks. That is, when they are not “policing” the other dogs by getting vocal and trying to step in if other dogs are, in the Shepherd’s mind, playing too rough. I laughed out loud the first time I watched Scout play with another Corgi! The style he adopted was to jump and fling his rear end into the other Corgi and then hop away, kind of like a bunny – a behavior I had never seen from Scout before in play with the bigger dogs! If your dog isn’t used to, or comfortable with, one of the play styles being displayed by another dog at the dog park, it can go from bad to ugly pretty quickly. This is why it’s super important to monitor your dog the entire time he’s at the dog park – so you can see firsthand how he responds to other dogs of various breeds and sizes coming up to him, initiating play with him (or vice versa) and making sure that everyone is showing they are having a good time.

Lastly, there can also be a safety issue for young pups (or elderly dogs) at the dog park. Puppies still have growing bones and muscles that are more fragile than those of adult dogs, and seniors have weaker bone structure in their older age. Both can more easily be rough-housed by other dogs and result in injury. Young pups and seniors may also have compromised immune systems and are more susceptible to catching diseases from other dogs (one of the reasons it’s appealing to attend a dog park that requires proof of vaccination for any dog park users). Something to keep in mind.

Where Scout once appeared fond of this type of play, he started to become more assertive and vocal with the bigger dogs when they would cause him to tumble. It appeared he no longer enjoyed being the object of the bigger dogs’ attention. He started standing up for himself more, which is natural to a certain degree, but there were times when I felt his strong reactions were unwarranted. I realized that having this kind of experience with the other dogs was no longer helping Scout to become comfortable with other breeds; instead, it was causing him to feel like he had to become defensive all the time so the bigger dogs wouldn’t pick on the little guy. As soon as I made this realization that being in the BDA at lunchtime was beginning to have a negative effect on my dog, I decided we would no longer take part in this ritual.

Now that’s not to say that Scout doesn’t enjoy running free with other dogs anymore. As a dog owner, I just take my responsibility seriously to ensure that I don’t put my dog in any situations that are too much for him. This means that instead of running amok in a dog park with many unknown dogs, Scout spends his outdoor time with his canine friends by going on walks or hiking together, usually only a few other dogs at a time – which is what he loves and can handle. This is just who he is. He enjoys when I use him to help clients and their dogs have positive dog exposure sessions – he takes his job as cohort very seriously! Plus, when hiking or walking the dogs have something else to focus on other than one another – they wander and sniff and do other natural dog things, taking the pressure off of the dog-to-dog interaction. Scout has had a 100% success rate getting along with other dogs when using this method, and he actually looks forward to doing this with some of his best buds! For more info on how to make this work for your dog, contact me or see my article Introducing Fido to Rufus: Dog Greetings, Pressure Free!

Something else you might witness at dog parks: different breeds having different play styles. For example, we used to joke at Guiding Eyes that a Lab’s version of play is “let’s mesh spleens!” since they often can be found enthusiastically body-slamming one another; while a Shepherd tends to play herding games by nipping at heels or hocks. That is, when they are not “policing” the other dogs by getting vocal and trying to step in if other dogs are, in the Shepherd’s mind, playing too rough. I laughed out loud the first time I watched Scout play with another Corgi! The style he adopted was to jump and fling his rear end into the other Corgi and then hop away, kind of like a bunny – a behavior I had never seen from Scout before in play with the bigger dogs! If your dog isn’t used to, or comfortable with, one of the play styles being displayed by another dog at the dog park, it can go from bad to ugly pretty quickly. This is why it’s super important to monitor your dog the entire time he’s at the dog park – so you can see firsthand how he responds to other dogs of various breeds and sizes coming up to him, initiating play with him (or vice versa) and making sure that everyone is showing they are having a good time.

Lastly, there can also be a safety issue for young pups (or elderly dogs) at the dog park. Puppies still have growing bones and muscles that are more fragile than those of adult dogs, and seniors have weaker bone structure in their older age. Both can more easily be rough-housed by other dogs and result in injury. Young pups and seniors may also have compromised immune systems and are more susceptible to catching diseases from other dogs (one of the reasons it’s appealing to attend a dog park that requires proof of vaccination for any dog park users). Something to keep in mind.

|

THE UGLY:

Let’s face it… some owners enjoy bringing their dogs to the dog park so they themselves can socialize with friends. But if owners are too busy socializing themselves and not paying attention to the body language that their dog is exhibiting, it’s easy for signs that a dog is uncomfortable to be missed until it’s too late. Perhaps the owner is a new dog owner and doesn’t know much about canine body language. Or, a situation that starts out fine escalates quickly and an owner isn’t aware in enough time to step in and dissipate the situation before an annoyed dog “has words” with another dog. |

What to watch for: A shy or unsocial dog is often an easy target for a more assertive dog (kind of like how a bully on a playground can easily pick out the quiet kid in the corner playing by himself). Watch for a dog that is feeling terrorized by another dog by showing signs such as hiding behind your legs, under a bench, or trying to retreat to a quiet corner. If this situation isn’t dissipated and the other dogs aren’t redirected by their owners quickly, the dog that is trying to hide may feel threatened and, if nobody else comes to the rescue and he is passing the threshold of what he can handle, he is going to stand up for himself. Unfortunately, that usually comes in the form of a nip or bite. This dog doesn’t mean to be aggressive, but when “fight or flight” are your only options, and he tried to flee to no avail, fight is next on the list.

Also watch for an assertive dog that is persistent about playing with, jumping on, or mounting other dogs. This kind of dog usually has a highly activated arousal level, which means he’s not really taking good notes from the other dogs when they tell him enough is enough. It’s natural for a dog that doesn’t want to be ridiculed or mounted anymore to try to “tell off” the persistent dog, but if that persistent dog’s arousal level is extremely high, it may escalate into a fight of authority pretty quickly before anyone really knows what’s going on or which dog started it.

Also watch for an assertive dog that is persistent about playing with, jumping on, or mounting other dogs. This kind of dog usually has a highly activated arousal level, which means he’s not really taking good notes from the other dogs when they tell him enough is enough. It’s natural for a dog that doesn’t want to be ridiculed or mounted anymore to try to “tell off” the persistent dog, but if that persistent dog’s arousal level is extremely high, it may escalate into a fight of authority pretty quickly before anyone really knows what’s going on or which dog started it.

If you are going to take your dog to a dog park, here are some ways to set your dog up for success:

- Calmly and matter-of-factly walk your dog to the dog park entrance area (many have a separate smaller area where you can unhook your dog’s leash and then enter the larger part of the park). This means quiet and purposeful movements, not ramped up excitement about what you and your dog are about to do or which friends you are about to see. Since dogs pick up a lot from our own energy, if you are activated or nervous, your dog will start out that way right off the bat as well; whereas maintaining a relaxed and methodical persona will help your dog remain thoughtful as well.

- Require that your dog sit and remain seated as you unhook his leash. ONLY when your dog is truly calm (and no, sitting but shaking uncontrollably or whining with excitement doesn’t count) should you reach to open the gate. Slowly and calmly begin to open the gate as your dog holds his seated position. This may take several bouts of practice for your dog to figure out that the gate only opens further if he can maintain his patience and self-control. If he breaks his sit, gently step in front of your dog and close the gate, then redirect him to sit once again. If there’s a line of people behind you waiting to get in, put your dog back on leash, let the other people go first, and then try again. Once the gate is opened, it’s good practice that your dog waits to enter until you release him (and do it nonchalantly, not like you’re letting a bull out of the gate at a rodeo).

- Watch your dog’s behavior upon entering the park. If your dog goes right up to the action of where the other dogs are, go with your dog and keep yourself in calm motion as your dog introduces himself to the other dogs. I say “stay in motion” because if you stand and stare at your dog, this usually escalates a greeting to involve a lot of pressure. Whereas if you move about freely, the experience itself can also be freeing for your dog, as he will pick up on your confident energy and exude that same confidence and calmer energy himself.

- If your dog sticks to the perimeter of the park and is hesitant to approach other dogs (especially if this is his first time in the park), accompany your dog on his exploration. You are not there to point everything out to your dog, but rather to let him explore on his own and at his own pace – you are passive support. This lets your dog know two things: 1) that you’ve got his back and you’re in this together, and 2) you aren’t going to throw him into the fire by putting him into situations that he’s not ready for by himself. Both of these instill feelings of trust and respect – critical components to any human-canine relationship.

- Once your dog is comfortable in his surroundings and with the other dogs within the park, it’s also a good idea to occasionally (maybe every few minutes) either go up to your dog or encourage your dog to come to you, and give your dog a lot of praise. You may also use treats if you choose but be sure to be aware of the dog park’s rules – some parks prohibit use of treats of any kind. Throwing in these little breaks will bring your dog’s arousal level back to his baseline. It will also help your dog understand that even though he’s interacting with other dogs, you are still very much a part of his experience, and in a rewarding way. If he gets used to you coming up to him during playtime, and then releasing him to go play again, he will also learn that just because you approach him doesn’t mean playtime is over – and he will be more likely to come back to you when it is really time to go.

Now that you know the GOOD, the BAD and the UGLY truth about dog parks, you can determine whether or not a dog park experience will be beneficial for your dog. You also have a few pointers about setting an outing up for success. Good luck, and above all, much fun to you and your dog!

For more information on dog-to-dog socialization that will build up your dog's confidence around other dogs, appropriate play tactics and behavior, and how to stop the common barking and pulling/lunging issue, please contact me at (845) 549-0896 or [email protected]. I'm happy to say that the methods I use to do this have a very high success rate in teaching dogs to get along better with other dogs!

For more information on dog-to-dog socialization that will build up your dog's confidence around other dogs, appropriate play tactics and behavior, and how to stop the common barking and pulling/lunging issue, please contact me at (845) 549-0896 or [email protected]. I'm happy to say that the methods I use to do this have a very high success rate in teaching dogs to get along better with other dogs!

Written by Maria Huntoon, Maria G. Huntoon Canine Consulting Services